CFTC Initiates Enforcement Sweep Targeting Opyn and Other DeFi Operations

Coinbase-Backed Insurance Disruptor OpenCover Launches on Layer 2 Blockchain

DeFi and Credit Risk

In less than a decade, Web 3 has astonished the world by creating an alternative financial system with unprecedented freedom and inventiveness. Public key cryptography, smart contracts, proof-of-work, and proof-of-stake are examples of cryptographic and economic primitives, or building blocks, that have led to a sophisticated and open environment for describing financial transactions.

Humans and their relationships, however, provide the economic value that finance trades on. Web 3 has become fundamentally dependent on the very centralized Web 2 institutions it intends to transcend, repeating their constraints, because it lacks primitives to represent such social identity.

The lack of Web 3-native identity and reputation, for example, leads non-fungible token (NFT) artists to rely on centralized platforms like OpenSea and Twitter (TWTR) to commit to scarcity and initial provenance, and inhibits less-than-fully collateralized forms of loans. For resilience to Sybil attacks, distributed autonomous organizations (DAO) that strive to go beyond simple currency voting generally rely on Web 2 infrastructure, such as social media accounts (one or a few entities pretending to be many more entities). Many Web 3 players also rely on centralized wallets controlled by companies like Coinbase (COIN). It's no surprise that decentralized key management systems are difficult to utilize for all but the most advanced users.

In our paper, we show how even tiny and gradual efforts toward capturing social identity with Web 3 primitives can alleviate these problems and move the ecosystem much closer to renewing markets and the human interactions that underlie them in a native Web 3 context.

Even more promising, we show how native Web 3 social identity, combined with rich social composability, has the potential to make significant progress on broader, long-standing Web 3 issues like wealth concentration and governance vulnerability to financial attacks, while also sparking a Cambrian explosion of innovative political, economic, and social applications. We call these use cases "Decentralized Society" because they enable a more diverse pluralistic ecosystem (DeSoc).

Soulbound tokens

Accounts that hold publicly accessible, non-transferable (but possibly revocable by the issuer) tokens are the foundation of our system. This set of traits was chosen not because it is the most desirable set of features, but because it is simple to implement in the existing context and allows for extensive functionality.

The accounts are referred to as "Souls," and the tokens owned by the accounts are referred to as "Soulbound Tokens" (SBT). Despite our strong desire for privacy, we presume these will be publicly available at first because it is technically easier to validate as a proof-of-concept, even if the subset of tokens users are prepared to publicly publish is small. We'll talk about programmably private SBTs in the next section.

Consider a world where everyone has a Soul that stores SBTs that correspond to a variety of affiliations, memberships, and credentials. A Soul, for example, may hold SBTs reflecting educational qualifications, companies they've worked for, hashes of works of art or novels they've written, and so on. These SBTs can be "self-certified" in the same way that we publish information about ourselves in our resumes. When SBTs held by one Soul can be issued by other Souls who are counterparties to these relationships, the true potential of this mechanism is revealed. Individuals, organizations, or institutions could be the counterparty Souls.

A university, for example, may be a Soul that issues SBTs to graduates. A stadium may be a Soul that gives out SBTs to die-hard Dodgers fans.

It's worth noting that a Soul doesn't have to be tied to a legal name, nor is there any protocol-level attempt to assure "one Soul per individual." A Soul could be a persistent pseudonym for a variety of SBTs that are difficult to connect. We also don't think that Souls aren't transferable between humans. Instead, we strive to show how, when necessary, these features can arise naturally from the design.

Soul lending

Credit and uncollateralized lending are perhaps the most significant financial value generated directly on reputation.

Because all assets are transferable and saleable – thus just types of collateral – the Web 3 ecosystem currently cannot duplicate even the most fundamental forms of uncollateralized lending. Many forms of uncollateralized lending are supported by the traditional financial ecosystem, but they are frequently mediated through centralized credit scoring processes, with the argument that less-creditworthy borrowers have no motivation to divulge information about their creditworthiness.

However, such scores have numerous faults. At best, they obscure overweight and underweight creditworthiness determinants and skew people who lack sufficient data, primarily minorities and the poor. At worst, they can enable opaque "social credit" systems a la "Black Mirror," which design social consequences and encourage inequality.

A bottom-up, censorship-resistant alternative to top-down commercial and "social" credit systems could be unlocked by an SBT ecosystem. SBTs representing college credentials, previous employment history, and rental contracts, to name a few, might serve as a persistent record of credit-relevant history, allowing Souls to avoid the need for security by securing a loan based on their meaningful reputation. Loans and credit lines are non-transferable but revocable SBTs that are nested among a Soul's other SBTs – a kind of (non-seizable) reputational collateral – until they are repaid and burned (or, better yet, replaced with proof of repayment that augments the Soul's credit history). Consider it to be akin to a credit history note.

SBTs have useful security properties: non-transferability prevents borrowers from transferring or hiding outstanding loans, and the presence of a large ecosystem of SBTs ensures that borrowers who try to avoid their loans (perhaps by spinning up a new Soul) will be unable to stake their reputation meaningfully.

The simplicity with which SBTs can be used to calculate public liabilities could lead to open-source lending markets. New correlations between SBTs and payback risk would emerge, resulting in improved lending algorithms that anticipate creditworthiness, minimizing the importance of centralized, opaque credit-scoring infrastructure. Better yet, lending would most likely take place within social networks, resulting in new forms of communal lending. SBTs, in example, could provide a foundation for "group lending" techniques like those pioneered by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus and the Grameen Bank, in which members of a social network agree to support each other's liabilities. Participants could readily locate other Souls who would be desirable co-participants in a cooperative loan initiative since a Soul's constellation of SBTs symbolizes memberships across social groups. Community financing might take a "lend-it-and-help-it" approach, combining working capital and human capital with higher rates of return, whereas commercial lending is a "lend-it-and-forget-it" until payback model.

Not losing your soul

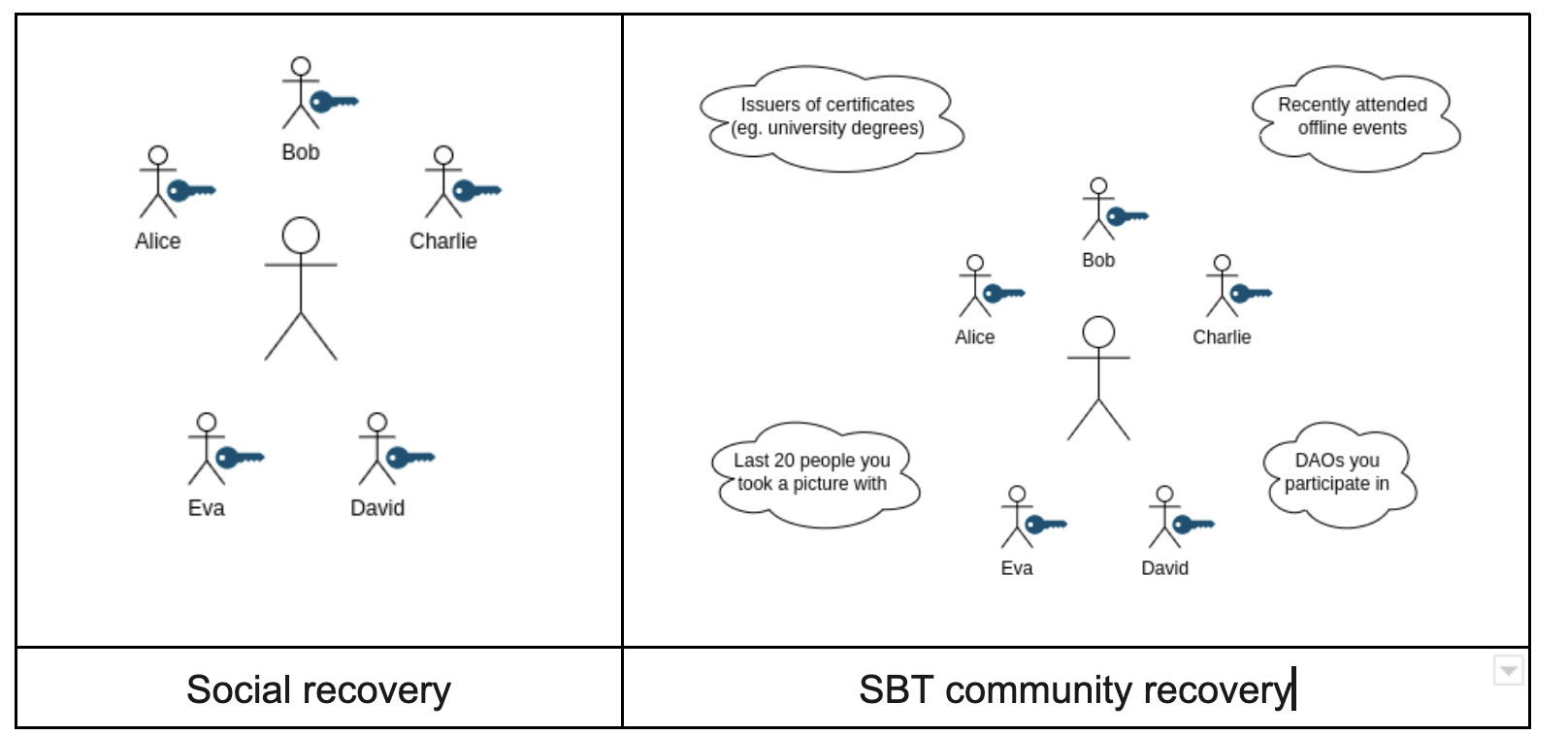

The non-transferability of major SBTs, such as one-time issued education credentials, begs an important question: How do you keep your Soul? Today's recovery approaches, such as multi-signature recovery or mnemonics, have varying mental burden, transaction convenience, and security trade-offs. Social recovery is a new option that is based on a person's trusted relationships. SBTs enable a similar but broader paradigm: community healing, in which the Soul represents the intersectional vote of its social network.

Social recovery is a wonderful place to start when it comes to security, but it has significant security and usability flaws. A user creates a group of "guardians" and grants them the power to modify the keys to a wallet by majority vote. Individuals, institutions, or other entities could serve as guardians. The issue is that a user must weigh the desire for a large number of guardians against the need for guardians to come from different social groups in order to avoid collusion. Also, guardians can die, relationships can break down, or people simply lose touch, necessitating frequent and attention-demanding updates. While social rehabilitation avoids a single point of failure, it does require cultivating and sustaining trusting relationships with the bulk of your guardians.

A more secure way would be to link Soul recovery to a Soul's memberships across groups, rather than curating but instead relying on a large number of real-time relationships. Remember that SBTs indicate distinct community affiliations. Employers, clubs, colleges, and churches are examples of off-chain communities, whereas involvement in a protocol governance or DAO is an example of on-chain communities. A qualified majority of a (random subset of) Soul's communities must consent in order to recover a Soul's private keys in a community recovery scheme. We assume, as with social recovery, that the individual has access to secure, off-chain communications channels that are larger than the chain itself and may be used for "authentication" (via dialogue and sharing of shared secrets). SBT-tokenized connections are frequently thought of as providing access to such channels.

From “Decentralized Society: Finding Web 3’s Soul,” by Glen Weyl, Puja Ahluwalia Ohlhaver and Vitalik Buterin.

Maintaining and recovering cryptographic possession of a Soul requires consent of the Soul’s network. By embedding security in sociality, community recovery deters Soul theft (or sale). A Soul can always regenerate their keys through community recovery. Thus, any attempt to sell a Soul will lack credibility because a Seller would also need to prove they sold the recovery relationships.

Programmable plural privacy

The most important data isn't always individual, but rather interpersonal (e.g., social graph) or only valuable when pooled in bigger groups (e.g., health data). However, proponents of "self-sovereign identity" see data as private property: I own the data about this interaction, so I should be allowed to choose when and to whom I release it. However, the digital economy is even less well understood in terms of simple private property than the physical economy. Even in basic two-way partnerships, such as an illicit affair, the right to reveal information is normally symmetrical, needing reciprocal consent and authorization. People sharing characteristics of their social graph and information about their friends without their agreement was at the heart of the Cambridge Analytica affair.

Rather than treating privacy as a transferable property right, consider it as a programmable, loosely tied set of rights to allow access to, edit, or profit from information. Every SBT has an implied programmed property right determining access to the underlying information creating the SBT: the holders, the agreements between them, the shared property or assets, and obligations to third parties, to name a few. Some issuers and communities will opt to make SBTs completely public, such as those that mirror information from a public CV. In the atomistic notion of verified credentials, some SBTs will be private. The majority will go somewhere in the middle, revealing some information publicly while keeping some information private while sharing some information with a select group.

SBTs make privacy a programmable, composable property right that can be mapped onto the current complex network of expectations and agreements. Better yet, SBTs assist us in imagining novel configurations, as there are an endless number of ways to combine privacy – as a property right to authorize access to information – to construct a complex constellation of access rights.

Holders of SBTs, for example, may use a specialized privacy-preserving mechanism to execute computations over data repositories, perhaps owned and regulated by a collective of Souls. Some SBTs may even allow authorization to access data in such a way that computation across data storage is permitted, but the contents can only be confirmed with the approval of a third party. This could be beneficial for SBTs that instantiate and describe "continuous voting" systems, in which the voting mechanism must tally votes from all Souls, but votes should not be provable to anyone else in order to prevent vote buying.

Healthy forms of the "attention economy" could be stewarded by SBTs, allowing Souls to filter spam inbounds from likely bots outside of their social network while promoting communication from authentic groups and desirable intersections. This would be a significant advance over today's communication platforms, which lack user control or governance and auction user attention to the highest ad bidder, even if that bidder is a bot. Listeners may become more conscious of who they are listening to and may be better able to credit works that generate new ideas.

Instead of focusing on engagement, such an economy might focus on positive-sum cooperation and valuable contributions.

The failures of man's "organizing force" to keep up with "his technical developments" had put a "razor in the hands of a 3-year-old kid," Albert Einstein said at a disarmament conference in 1932. Learning how to create futures that build on trust rather than replace it appears to be a mandatory course for human life on this planet to survive in a world where his perspective looks more prescient than ever.

=====