MicroStrategy's Significant Bitcoin Impairment Losses May Mislead: Berenberg

Turkish Crypto Exchange Thodex CEO Faruk Özer Sentenced to 11,196 Years in Prison for Collapse

DeFi and Credit Risk

Many bitcoiners scoffed at the concept of environmentalists launching a campaign to alter Bitcoin's code away from the energy-intensive proof-of-work (PoW) mechanism in March.

Leaving aside the matter of whether proof-of-work mining poses the environmental threat that environmentalists allege it does, many cryptocurrency veterans are skeptical that the method will succeed.

This method is based on persuading a small number of companies or individuals who, according to the activists, have the power to make the change or at the very least persuade a critical mass of others to support it.

This strategy appears to be ignorant of Bitcoin's history, particularly the block size wars of 2015-2017, which included the debate over the Segregated Witness (SegWit) upgrade, in which one of two proposed changes advocated by the largest firms failed due to massive user opposition.

The organizers of the "Change the Code, Not the Climate" campaign acknowledge this history and even use it as proof that change is possible.

Making sense of Bitcoin's past

The block size conflicts and the SegWit update "provide as a case in point" to demonstrate that "changes can be accomplished," according to Faber, senior vice president, government affairs at Environmental Working Group (EWG), one of the campaign's spearheaders. Whether these adjustments take the form of a "hard fork" or a "soft fork," he believes they can be implemented "when there is universal consensus among the Bitcoin community."

Rolf Skar works as a special projects manager for Greenpeace USA, an environmental advocacy group that is involved in the campaign. According to Skar, there are two crucial considerations to consider when determining whether the network can change: first, is it technically feasible? Skar told CoinDesk that the 2017 SegWit update "shows that it is, quite obviously, technically feasible to do so." The second question, he noted, is "whether a suggested change could be supported sufficiently to be implemented."

"Despite skepticism," added Skar, "the campaigners don't see a clear reason why enough support won't be garnered ultimately." "In order to address legitimate community concerns, solutions will need to be created and tested." We acknowledge that if appropriate solutions are not established, adoption of new code would be difficult," Skar stated.

Given how companies have sneered at other environmental initiatives, such as electric lorries, which were mocked at first but then sold in droves, a shift away from PoW may not seem so far-fetched, according to the advocates.

Ken Cook, the founder and CEO of EWG, believes that Bitcoin's governance has changed, and that there is now a "inexorable concentration of power and influence," based on his talks with key insiders in the Bitcoin business.

He claimed that the "idea that this was as democratic as it was originally envisaged" has vanished.

"Although it's a decentralized system, there are critical actors within it," Skar said of Bitcoin in an interview.

"The wealthiest 50 percent of miners control practically all mining capacity," according to a research published by the National Bureau of Economic Research in October 2021, according to EWG's Cook. "The top 10% control 90% of all bitcoin mining capacity, while the top 0.1 percent control close to 50%," according to the report, and "the top 55-60 miners control at least half of all bitcoin mining capacity."

Faber believes that the choice will not be decided by a group of 50 individuals, but that if Bitcoin leaders "raise their voices," they may assist start the dialogue that will eventually lead to the necessary adjustments.

Who is in charge of Bitcoin?

In 2015, a discussion on how to improve the Bitcoin network's scalability gained traction. Some developers and stakeholders advocated for a larger block size, while others believed it would hurt decentralization.

After two years of debate, the Bitcoin network's Segregated Witness (SegWit) update was approved via a soft fork, allowing users to continue using the old version of the program. By altering the way data is kept on the chain, SegWit boosted the amount of transactions the network could handle. Unlike prior ideas to raise block size, SegWit was well-received by users.

Another suggestion to expand the block size was rejected at the same time. At CoinDesk's 2017 Consensus conference in New York, 58 organizations signed an agreement representing 83.28 percent of the network's computing power. The agreement asked for the maximum block size of Bitcoin to be doubled to two megabytes. Four of the companies were actively involved in mining, including CoinDesk's parent company, Digital Currency Group (DCG), which also owns Foundry, a US miner. Mining pools made up the remaining seven signatories.

Six months later, however, the ostensibly strong signatories backed down and canceled the hard fork, or backward-incompatible code change, citing a lack of consensus. Bitcoin Cash is a breakaway network created by some big-block proponents.

Skar remarked that "five years is a long time in Bitcoin's very short existence" when asked about the block size debate and the fact that some modifications were never implemented. Things have changed, as have the challenges at hand." He believes that it is up to the individuals and players in the Bitcoin social ecosystem to decide how change will happen.

According to Faber, SegWit was implemented because the Bitcoin community recognized its importance to the network's success. According to the EWG vice president, Bitcoin now faces a new threat: regulation.

For the time being, "the Bitcoin community is in charge of deciding how to limit the amount of electricity needed by PoW and the related climate pollution." But only for a short time. "Regulators will not stand by while the climate problem worsens and digital currencies like bitcoin consume more and more electricity and emit more and more greenhouse gases," Faber added.

The difficulty of modifying Bitcoin by consensus

Even if it were possible, changing the protocol is only part of the picture. Achieving a "rough community consensus," according to Jonas Nick, a Bitcoin engineer with Blockstream who was involved in another big protocol change last year known as Taproot, was an important step for the upgrade to be deployed.

But, according to Nick, the key to modifying Bitcoin is persuading "an overwhelming majority of Bitcoin economic activity to use" the new code. "You can always change the laws of chess," the developer explained, "but you may have to play alone."

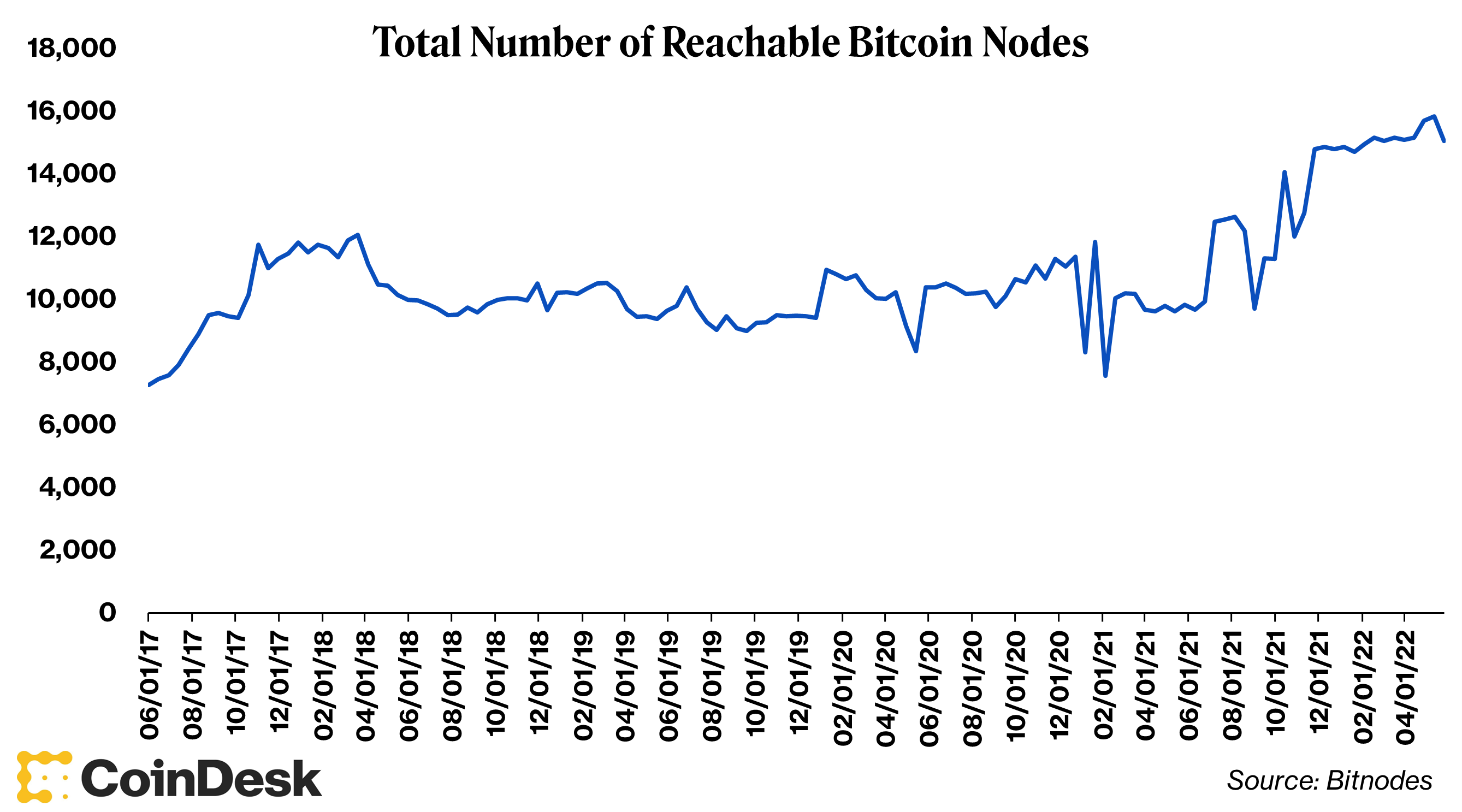

The total number of bitcoin nodes is higher than ever (George Kaloudis/CoinDesk).

The number of reachable nodes in the Bitcoin network is one indicator of its decentralization. The number of reachable Bitcoin nodes has increased by 27.5 percent since the end of 2017. The blocksize conflicts revealed that users have control over the protocol's direction, implying that more collaboration is required to make large-scale changes to the network.

When asked if it's possible to move Bitcoin away from PoW, Nick replied the Bitcoin community agrees that PoW "is the only known consensus algorithm that can fuel a decentralized currency."

People have tried to switch Bitcoin through various forks, according to Andrew M. Bailey, who teaches about cryptocurrencies at the joint Yale-National University of Singapore College, but the value of these coins tends to plummet "very, very quickly."

"What that implies is that the vast majority of Bitcoiners will just sell their forked proof-of-stake coin," he said, adding that "the only way to make it happen is to achieve social consensus" from the whole community.

This unanimity, according to Bailey, is "extraordinarily unlikely" since Bitcoin has a "conservative development culture," in which changes are made slowly and only when the community is certain of their consequences.

=====