Ripple's Acquisition of Crypto-Focused Chartered Trust Company Fortress Trust

MicroStrategy's Significant Bitcoin Impairment Losses May Mislead: Berenberg

Turkish Crypto Exchange Thodex CEO Faruk Özer Sentenced to 11,196 Years in Prison for Collapse

According to a recent scholarly report, Bitcoin (BTC) was more centralized and vulnerable in its first two years than previously thought.

According to the report, which was co-authored by nine experts from six institutions across the world, the cryptocurrency survived and prospered because of a tiny number of pioneers who opted not to attack the network when they could have easily done so. (Names and affiliations of the academics are included at the bottom of this post; one of them, Alyssa Blackburn, will talk at Consensus 2022 this week in Austin, Texas.)

As a result, the early years of Bitcoin provide a fascinating glimpse into anonymous party collaboration. "Anonymity is thought to impair cooperation in general because it interferes with the cooperative processes of reciprocity, relatedness, and reputation," according to the report. Surprisingly, the data demonstrates that despite though 64 parties controlled the majority of processing power during this period, they all operated in the network's best interests. Even if they had never met before.

To be clear, the research makes no specific assertions regarding the Bitcoin network's security now, well than a decade after the conclusion of the study period.

According to researcher Erez Lieberman Aiden, "we aimed to understand the socioeconomic process by which bitcoin transformed from a digital entity with no market to a working means of exchange." "As a result, we selected to investigate the time between the debut of Bitcoin and price parity with the US dollar: the 25 months following its launch."

Aiden explained that the types of data leaking studied in this study were chosen because they were relevant in researching that 25-month period.

"In the end, we discovered a lot of data leakage that we could exploit, which allowed us to do our research," he stated. "Obviously, Bitcoin has undergone a lot of changes since 2011!" As a result, some types of data leaking may be less effective now, while others may be more effective."

He did, however, mention that the study "was able to succeed due to a significant degree of information leaking from the blockchain during the period we analyzed." There's no reason to suppose the data leaking is restricted to the time period we investigated."

Nonetheless, given the novel address-linking techniques used by the researchers – and, more broadly, about the motivations that enable decentralized networks to function – the paper, which has been covered by the New York Times, is likely to spark heated debates about long-standing challenges to Bitcoin network users' privacy – and, more broadly, about the motivations that enable decentralized networks to function.

64 bitcoin miners in a group

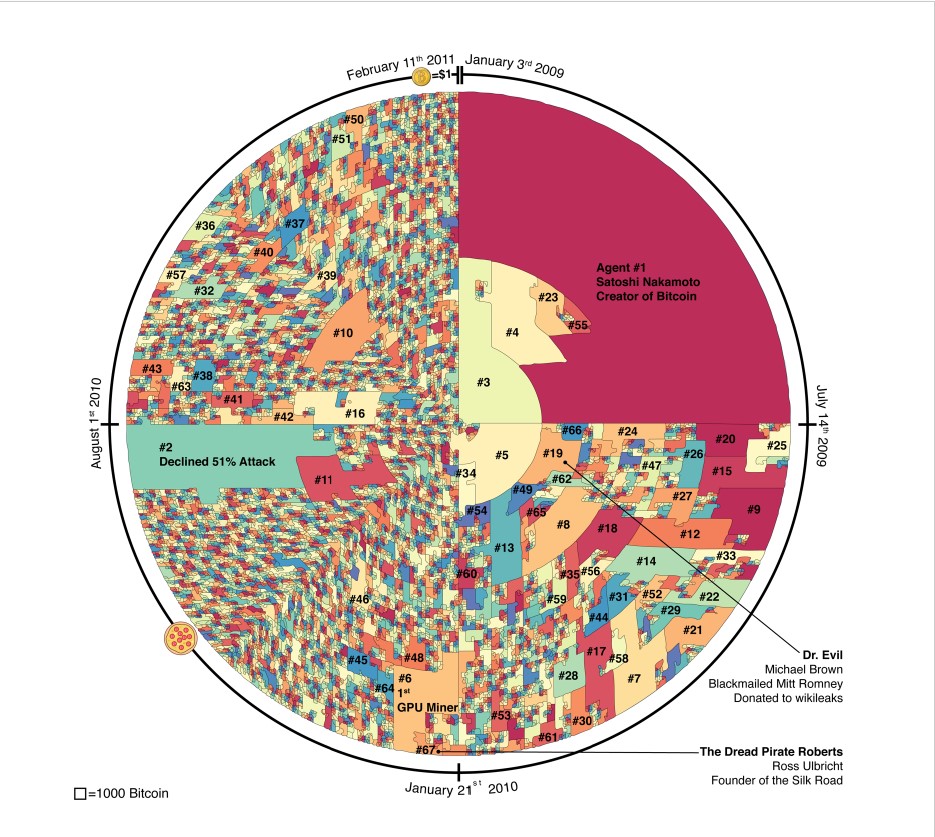

According to the analysis, 64 different individuals mined a large share of the BTC generated between Jan. 3, 2009, when the currency was first introduced, and Feb. 9, 2011, when its price reached $1.

Each mining agent is represented by a tile with an area proportional to the quantity of bitcoin they mined. Those tiles are positioned in the circle in a clockwise direction according to the time when those agents mined their first bitcoins. The 64 agents who mined the most bitcoin in the 25-month time frame are identified in descending order by size. (Blackburn, Huber, Eliaz et al.)

This period before the introduction of ASICs, or specialized mining equipment (application-specific integrated circuits). Early adopters mined BTC with normal home computers' central processing units, and then with the more powerful graphics processing units favored by gamers.

The researchers were able to identify pseudonymous Bitcoin addresses that were all controlled by the same people because to the quirks of these early mining systems, according to the report.

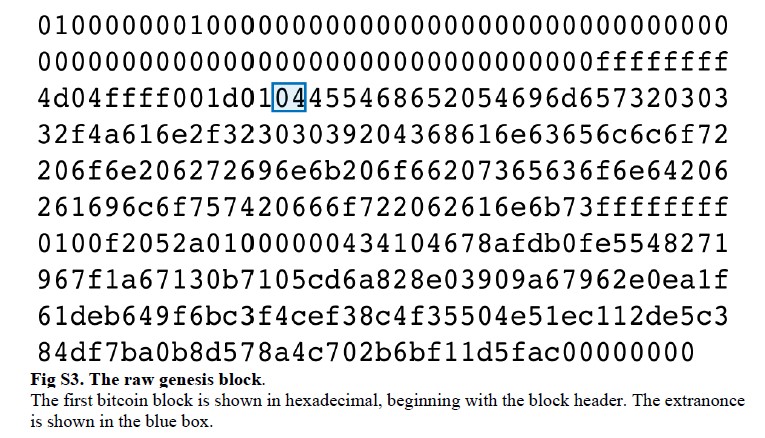

To effectively mine BTC, a computer must generate a nonce, which is a string of integers that, when fed into a mathematical formula with a few other inputs, generates an output that is less than a particular target. According to the article, early miners' computers left "fingerprints" on the nonces they created, much as unique persons have different handwriting patterns (even if they write gibberish).

"All of the seemingly insignificant strings connected with a single user have enormous relationships," it reads. The researchers were able to pinpoint the miners that mined much of the first 25 months' worth of BTC and produced those early transaction addresses using these "extranonces" in combination with other well-established blockchain forensic tools.

To arrive at the group of 64, the researchers integrated such correlations with a handful of well-known address-linking algorithms.

(Blackburn, Huber, Eliaz et al.)

Bitcoiners with a good heart

The fewer miners there are, the more likely it is for one to control the network, or for many miners to join together to do so. The paper claims that due to the tiny number of miners during Bitcoin's early years, the network was "routinely" vulnerable to so-called 51 percent assaults, in which someone with a simple majority of computer power may spend the same BTC twice.

Three of the 64 "top agents," for example, each mined six or more blocks in a succession. According to the analysis, there were five six-hour intervals in October 2010 during which one miner, one of the first to employ a GPU, could have carried out a 51 percent attack.

The emphasis is on the word "could."

The researchers concluded, "Strikingly, we discover that potential attackers invariably choose to collaborate instead."

On the one hand, their conclusion contradicts the stereotype (and, in some cases, self-image) of Bitcoin users, particularly early adopters, as cold-blooded individualists: "Rather than relying exclusively on a decentralized, trustless network of anonymous actors, Bitcoin relied on altruistic behavior by a group of anonymous agents," according to the paper.

Sergio Demian Lerner, head of innovation at IOVLabs, a blockchain technology business, and a designer at RSK Labs, a smart-contract creation firm, has previously made similar observations. Lerner looked into the so-called "Patoshi hoard" of 1.1 million BTC that Satoshi Nakamoto is thought to have mined. In a research published in 2020, Lerner stated that early miners (particularly, "Patoshi") made steps to encourage healthy mining competition while also guaranteeing that there were enough miners active to safeguard the network and create blocks on schedule.

This paper also details game-theory studies whose findings support the idea that anonymous actors will collaborate for the welfare of the group rather than betray one other for a quick cash. Of course, "the good of the community" in the context of a cryptocurrency might be understood as ongoing price increases, and the study raises an unpleasant issue in the midst of what looks to be a bear market: "Can members be depended upon to cooperate if a cryptocurrency stops appreciating?"

Implications for Bitcoin Privacy

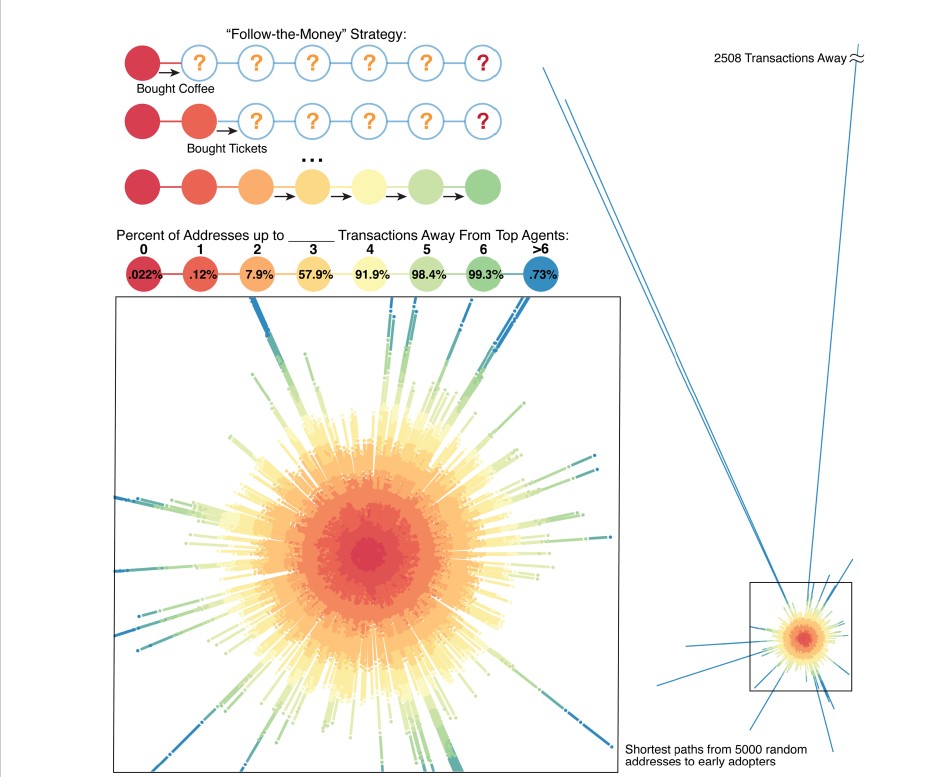

According to the study, 99 percent of Bitcoin network addresses were just six transaction hops away from one of the 64 early miners as of December 2017. (If Bob gives 1 BTC to Alice, it's one hop; if Alice transmits the coin to Ted, it's two hops, and so on.)

Although the researchers do not claim to have discovered the genuine identity of any of the 64 miners (except for two who were already known), they do warn that if they do, the privacy of many other users might be jeopardized.

"Our findings suggest that if the names of the 64 top agents were made public, it would be quite simple to uncover short transaction pathways tying any target address to an already de-identified top agent address," the paper concludes.

The authors point out that the shorter the path between two addresses, the easier it is for someone who knows one user's identity to deduce the identity of the other. If the FBI suspects Ted is a drug lord, it can subpoena Alice's transaction history from the crypto exchange she used to transfer him the BTC in the case above. From there, the feds may only need to research the address that sent her the coins to discover it publicly posted in Bob's tip jar.

At the very least, the researchers' address-linking experiment highlights a well-known vulnerability associated with utilizing public, unchangeable ledgers such as the Bitcoin blockchain. "Even once detected, the sources of information leaking cannot be rectified retrospectively," the report states.

"The fact that we were able to detect leaks throughout the time period we looked at implies that there may be leaks elsewhere as well," Aiden concluded.

Over 99% of bitcoin addresses studied between 2008 and 2011 fall within six transactions of bitcoin’s 64 top agents. (Blackburn, Huber, Eliaz et al.)

America-based Satoshi?

The researchers stay clear of the minefield of trying to figure out who Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin's founder, is. Since he (or she or they) published the first white paper in 2008, his (or their) identity has been a passionately contested enigma.

They do, however, repeat a previously analyzed data point that might provide a hint. Or maybe not.

Satoshi's emails, forum postings, and code changes were often transmitted during the daytime hours in the Western hemisphere, and his (or her or their) mining machine was normally dormant at night in that area of the world.

The researchers add, "These facts are consistent with Satoshi Nakamoto's possible residence in either North or South America."

They don't rule out the likelihood that Satoshi, like many other programmers, was a night owl.

=====